Wine Literature of the World

Europe and the United KingdomMost of the countries which use controlled wine appellations are European— Austria, Croatia, Cyprus, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Portugal, Romania, Spain and Switzerland. Of these, France is the country which sets the international standards by which wine is judged. Only Germany's riesling, Spain's sherry and Portugal's port are the non-French wines to be accepted as universal models. Wines like Chianti or Rioja remain vernacular styles, while burgundy and champagne are wines which other countries produce to the best of their ability using traditional grape varieties.

FranceFrance is both a model and a point of departure for vignerons around the world. Her dedication to enshrining the unique characteristics of her wine producing areas and insistence on rules which govern every aspect of winemaking produce the most famous wines in the world. It is probably fair to say that the French have inspired (and sometimes infuriated) the newer non-European wine producing countries to independently create their own wine styles.

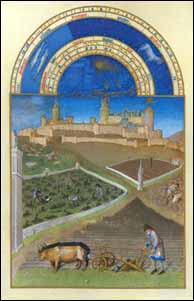

Some of the most beautiful images of winemaking appear in the calendar of Les très riches heures du Duc de Berry which was begun early and finished late in the 15th century for Jean, Duc de Berry. The miniature for March shows three peasants trimming vines within an enclosure, with more vineyards on the right. The miniature for September shows the grape harvest at the foot of the Château de Saumur. The original book is in the collection of the Musée Condé, Chantilly in France. The images from this book of hours have been widely used over the years these appear in a well known publication published in London by Thames & Hudson in 1969. Alexander Henderson's The history of ancient and modern wines (London, 1824) has an overview of the Wines of France, of which the first three pages are included here. Three important books on French vineyards are:

Of particular interest to Australians is Journal of a tour through some of the vineyards of Spain and France (Sydney: Stephen and Stokes, 1833) by James Busby, the father of Australian viticulture. The Library's copy was owned by South Australian winemaker Leo Buring. The journal is a fascinating account of a three month trip mainly by stagecoach to find the right vine varieties for planting in Australia. An appendix details the main French grape varieties Busby encountered. The latter half of the 19th century was the heyday of the illustrated books on wine. A delightful example is La vigne, voyage autour des vins de France : étude physiologique, anecdotique, historique, humoristique et même scientifique by Bertall (Paris: E. Plon, 1878). Bertall is the pseudonym of Charles Albert Arnoux, a celebrated artist and illustrator. His 659 page book is today much sought-after and very scarce.

The great French scientist, Louis Pasteur, made two discoveries of immense importance to winemakers. One was that fermentation is due to the action of yeasts in reproducing. The other was that when wine is exposed to air its resident bacteria take over and sooner or later the wine turns to vinegar. Pasteur's solution was to heat the wine in its bottle for long enough to kill the bacteria or microbes. Pasteurization also prevents further fermentation and stabilizes the wine. The first publication of his landmark work, Études sur le vin, ses maladies, causes qui les provoquent, procédés nouveaux pour le conserver et pour le vieillir (Paris: A L'Imprimerie Imperiale, 1866) shows equipment for testing the action of oxygen on red wines. Pasteur inspired a closer study of the medical uses of wine, and it has been said that 'after Pasteur, winemaking moved from art to science, the science of the chemist, just as grape-growing was in the hands of the botanist' (Eberhard Buehler in Wayward tendrils January 1998). Pasteur also wrote: 'Wine can be considered with good reason as the most healthful and the most hygienic of all beverages'. The French chemist, Jean-Antoine-Claude Chaptal, comte de Chanteloup, is remembered today for giving his name to the process of adding sugar to the grape juice to increase the alcoholic content of the wine Chaptalization. Chaptal was Napoleon's Minister of the Interior, and was possibly the first wine writer to work from the evidence of current day science rather than from the classics. His works such as L'art de faire, gouverner, et perfectionner les vins (Paris: Delalain fils, 1801) were to be drawn on by the father of Australian viticulture, James Busby. Dr Jules Guyot's study of the vineyards of France, Etude des vignobles de France: pour servir a l'enseignement mutuel de la viticulture et de la vinification françaises appeared in 1868 in three hefty volumes detailing the wine making practices of each area, including the idiosyncracies of pruning techniques, in which he had a particular interest. He wrote his own treatise on how it should be done in Culture de la vigne et vinification of which the Library holds the 3rd edition of 1864. He advocates a much simplified style of training vines, which found a strong following in Australia. In 1865 a translation was made in Australia by L. Marie as Culture of the vine and wine making in 1865. The Library's copy of the book was owned by South Australian winemaker John Reynell (his signature is on the flyleaf) and he has annotated it with his own notes relating to Australian conditions.

It was not until 1932 that the Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée (AC or AOC) was introduced which, among other things, limits production to a set amount per hectare. The nature of AC control varies region by region, with Burgundy the most specific. The complex system of French classifications, the concept of a chateau and the regional variations is not detailed here. Briefly, there are three levels of specific quality control for French wines above the basic Vin de Table level. At the top is the Appellation d'Origine Contrôlée (AC) to which all the great classics belong. The second level is Vin Délimité de Qualité Supérieure (VDQS), and many wines after a probationary period at this level are promoted to AC. The third level, Vin de Pays, was created in 1968 to give a geographical identity and quality yardstick to a range of wines, which is a useful category for adventurous winemakers wanting to use grapes not traditional to a particular area. There are seven major areas of control in the AC regulations, which are mirrored in some way in both VDQS and Vin de Pays. These are land, grape, alcoholic degree, vineyard yield, vineyard practice, winemaking practice, and testing and tasting. The main wine regions of France are Bordeaux, Burgundy, Champagne, Alsace and Rhone. Bordeaux The Bordeaux region of France was the first in the 19th century to have purpose-written books about it which list and categorise all the main vineyards and wines of that region. It remains the area documented in most detail over the years, covering the famous Médoc, Graves, Sauternes, St Emilion and Pomerol districts. The first major book dealing solely with the wines of Bordeaux was Traité sur les vins du Médoc et les autres vins rouges et blancs du département de la Gironde by a German winebroker, William Franck in 1824, of which the Library holds the 5th edition of 1864 (Bordeaux : P. Chaumas, 1864).

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Germany

German

climate varies from north to south and also from west to east. The east

has a more continental climate, a climate of extremes, while the north-west

regions like the Mosel, the Rheingau and the Rheinplatz produces the flagship

German grape, the hardy Riesling. The most planted grape is the Müller-Thurgau,

a cross betweeen Riesling and Sylvaner, folowed by the Sylvaner and the

Kerner. Eighty per cent of the German vineyard is white. Of the reds, Spätburgunder

(or Pinot Noir) is the most widely planted.

German

climate varies from north to south and also from west to east. The east

has a more continental climate, a climate of extremes, while the north-west

regions like the Mosel, the Rheingau and the Rheinplatz produces the flagship

German grape, the hardy Riesling. The most planted grape is the Müller-Thurgau,

a cross betweeen Riesling and Sylvaner, folowed by the Sylvaner and the

Kerner. Eighty per cent of the German vineyard is white. Of the reds, Spätburgunder

(or Pinot Noir) is the most widely planted.

Alexander Henderson's The history of ancient and modern wines (London, 1824) has an overview of the Wines of Germany and Hungary, of which the first three pages are included here.

Germany is divided into 13 Quality Wine regions, which are divided into Bereiche, which in turn are divided into around 150 Grosslagen a group of vineyards. German wine law grades wines according to the amount of sugar present in the grapes at harvest, on the principle that riper grapes are a sign of quality. With the worldwide trend toward drier wines both white and red wines in Germany are becoming drier and there is something of a revolution in grape growing in this country.

The

'Auslese' or 'first gathering' is described in a chapter on Rhine and Moselle

by Thomas George Shaw in the charmingly illustrated Wine,

the vine and the cellar 2nd edition (London: Longman, 1864), Shaw's

reminiscences and anecdotes of 42 years in the wine trade. 'The grapes

are usually gathered by women and children, who carry them to the intersecting

footpaths, where men are waiting to receive them, who immediately throw

them from the baskets into a small perforated tub, in which a boy treads

and crushes them so that all pass through the holes into the larger tub

below.'

The

'Auslese' or 'first gathering' is described in a chapter on Rhine and Moselle

by Thomas George Shaw in the charmingly illustrated Wine,

the vine and the cellar 2nd edition (London: Longman, 1864), Shaw's

reminiscences and anecdotes of 42 years in the wine trade. 'The grapes

are usually gathered by women and children, who carry them to the intersecting

footpaths, where men are waiting to receive them, who immediately throw

them from the baskets into a small perforated tub, in which a boy treads

and crushes them so that all pass through the holes into the larger tub

below.'

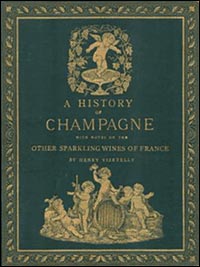

Henry Vizetelly describes the sparkling

wines of Germany in Facts

about champagne and other sparkling wines: collected during numerous visits

to the champagne and other viticultural districts of France, and the principal

remaining wine-producing countries of Europe (London:

Ward, Lock, 1879)

Mosel

Mosel

The

life of the Moselle: from its source in the Vosges Mountains to its

junction with the Rhine at Coblence by Octavius Rooke is illustrated

with seventy engravings from original drawings by the author engraved

by T. Bolton (London: L. Booth, 1858).

Rhine

Rhine

Ampélographie rhenane: ou description caracteristique, historique, synonymique, agronomique et économique des cépages les plus estimés et les plus cultivés dans la vallée du Rhin, depuis Bale jusqu'à Coblence, et dans plusieurs contrées viticoles de l'Allemagne méridionale by J. L. Stoltz (Paris: Dusacq, 1852) is also well illustrated.

Italy

The history of Italian wine is synonymous with the history of Italian civilisation. The ancient Greek name for much of Italy was Oenotria or land of trained vines. Alexander Henderson's The history of ancient and modern wines (London, 1824) talks about wine in the times of the Romans as well as a giving an overview of the 'modern' Wines of Italy and Sicily, of which the first three pages are included here.

Italy

has a vast number of soil types, climates, altitudes and grape varieties,

many strictly localised. It has a mountain range reaching south and east

from the Alps towards the subtropics. The dominant soils are calcareous

and volcanic, both productive for vines. Vineyards are cultivated virtually

everywhere, from the northern Alps to the southern islands, but mainly

on hillsides, 'vertical' growing compared to France's 'horizontal' growing.

Italy

has a vast number of soil types, climates, altitudes and grape varieties,

many strictly localised. It has a mountain range reaching south and east

from the Alps towards the subtropics. The dominant soils are calcareous

and volcanic, both productive for vines. Vineyards are cultivated virtually

everywhere, from the northern Alps to the southern islands, but mainly

on hillsides, 'vertical' growing compared to France's 'horizontal' growing.

Together with the many small producers it means that Italian wines have an almost infinite variety of flavours. Wine is part of the Mediterranean way of life and viticulture itself has always been part of a wholistic system of agriculture where vines, olives and grains were grown together in a polyculture. It is only during replanting of vineyards that the monoculture necessary for mechanisation is being seen.

In 1963 a classification system was introduced the Denominazione di Origine Controllata (DOC). Each of the 20 regions in Italy (95 provinces) produces wine and there are now around 250 classifications. Vineyards have been such a basic part of life for thousands of years at the local level that wine has not been seen as something for the connoisseur. Newer winemakers are developing new styles of wine, but the bottom line is that Italy has been happy to produce a basic quality of wine to satisfy local expectation, or for blending via export.

Italians have continued to use traditional

indigenous grape varieties, as well as a greater variety than probably

any other country. Of the most common 20 grape varieties, Sangiovese is

the most planted, followed by the Sicilian white grape Catarratto, the

central white Trebbiano Toscano, and Piedmont's Nebbiolo and Barbera. In

recent years plantings of varieties such as Pinot and Chardonnay have followed

international trends.

Italians have continued to use traditional

indigenous grape varieties, as well as a greater variety than probably

any other country. Of the most common 20 grape varieties, Sangiovese is

the most planted, followed by the Sicilian white grape Catarratto, the

central white Trebbiano Toscano, and Piedmont's Nebbiolo and Barbera. In

recent years plantings of varieties such as Pinot and Chardonnay have followed

international trends.

The oenographical output of Italy has been rather less than other countries. Pliny covers viticulture extensively in Book 14 of his Natural history, first printed in Venice in 1469, which includes various kinds of wines made in Italy and elsewhere from earliest recorded times to the first century A.D. The Library holds several editions of this great work, the earliest being in the original Latin in 1472 and an English translation in 1855 .

Since Andreas Baccius's opus of 1596 De naturali vinorum historia; de vinis Italiae. . . (but not held by the Library), the first general treatment of Italian wines in over 350 years is The wines of Italy by Luigi Veronelli in 1955 (Rome: Canesi Editore, 196-?).

Chianti

is the wine that most people associate with the romance of Italy and Tuscany

in particular. It is made from red Sangiovese, and there is no white

Chianti. Tuscany has been selected from a Descriptive

account of the wine industry of Italy by Giovanni Battista Cerletti

translated by Guido Rossati (Rome: Societa Generale dei Viticoltori Italiani,

1888). Among other titles the Library also holds Atlante del Chianti

classico : le fattorie del Gallo nero by Enrico Bosi of 1972.

Chianti

is the wine that most people associate with the romance of Italy and Tuscany

in particular. It is made from red Sangiovese, and there is no white

Chianti. Tuscany has been selected from a Descriptive

account of the wine industry of Italy by Giovanni Battista Cerletti

translated by Guido Rossati (Rome: Societa Generale dei Viticoltori Italiani,

1888). Among other titles the Library also holds Atlante del Chianti

classico : le fattorie del Gallo nero by Enrico Bosi of 1972.

Some of the other Italian wine regions are:

- Veneto, whose vineyards of Soave, Valpolicella and Bardolino make it the wine capital of Italy, holding its biggest wine fair Vinitaly in April

- Emilia-Romagna, with its capital Bologna the food capital of Italy, has the central Po valley which is Lambrusco country

- Latium, and the hills of Rome which produce Frascati

- Apulis, the heel and hamstrings of Italy are its most productive wine regions, mainly for blends for northern wines. The whites are subsumed into vermouth

- Sicily, which produces wine destined to be blended or to become vermouth. Its indigenous grapes are Catarratto or Inzolia which produce successful light crisp whites. It also produces Marsala.

Spain

Wine classifications are straightforward in Spain. Every region has vineyards and most use the same grapes Albarino and Verdejo for whites, and Tempranillo is the only commonly grown top red grape.

Rioja

is the leading wine region producing mainly red wines in the north of the

country. As a wine region, Rioja has a longer history than Bordeaux with

the land around the River Rio Oja ideal for winemaking.

Rioja

is the leading wine region producing mainly red wines in the north of the

country. As a wine region, Rioja has a longer history than Bordeaux with

the land around the River Rio Oja ideal for winemaking.

Andalucia in the hot south of Spain is the Jerez sherry region of Spain. The chalky white albariza soil soaks up and stores the winter rainfall, producing high yields from the Palomino Fino grape which is most commonly used for sherry.

Castilla-La Mancha is a tableland in central Spain near the capital Madrid. Its summers are hot and dry and winters very cold. The region of La Mancha is planted with so much of the robust white wine vine Airén that it is the world's most planted vine.

Catalonia is almost another country, with a separate language. It produces sparkling wine and quality still wine. Cava is the Catalan word for cellar and is applied to the Champagne method sparkling wines of the whole of Spain.

Alexander Henderson's The history of ancient and modern wines (London, 1824) has an overview of the Wines of Spain, of which the first three pages are included here. He talks about Spain's natural advantages of climate and soil, but goes on to note that 'in all those districts where a good system of management prevails, the vintages are distinguished by their high flavour and aroma, as well as by their uncommon strength and durability; in others these natural advantages are lost by adherence to erroneous modes of treatment'.

In his Notes on vineyards in America and Europe (Adelaide: L. Henn & Co, 1885) Thomas Hardy talks about being taken to bodegas (the Spanish name for a wine cellar or a winery, or also a tavern or grocery store selling wine) tasting many different types of sherry. 'The samples are all taken from the bung in a small silver cup, lashed to a whalebone handle about two feet long. The cellarman lets the wine fall into the glass from a considerable height without spilling a drop.'

This

illustration of 'A Jerez arumbador handling the venencia' is from Facts

about sherry of the Jerez, Seville, Moguer, and Montilla districts... which

is bound with The wines of the world characterized & classed: with

some particulars respecting the beers of Europe by Henry Vizetelly

(London: Ward, Lock, & Tyler, 1875).

This

illustration of 'A Jerez arumbador handling the venencia' is from Facts

about sherry of the Jerez, Seville, Moguer, and Montilla districts... which

is bound with The wines of the world characterized & classed: with

some particulars respecting the beers of Europe by Henry Vizetelly

(London: Ward, Lock, & Tyler, 1875).

The venecia is used in Spain, especially

in Jerez de la Frontera, to take samples from sherry casks. The silver

cup is attached to a pliable whalebone handle. The one illustrated here

was a gift to the Library by Dr Bryce Rankine.

![]()

Traditionally,

grape-treaders in Spain wear special cowhide boots, or Zapatos de pisar,

whose soles are heavily nailed with large-headed tacks driven into the

leather at an acute angle. This method of nailing gives results similar

to bare feet but with much less discomfort. The pips and stalks are trapped

undamaged between the nails and a soft layer of grapeskins forms over the

soles so that the hard pips and stalks of the other grapes cannot be broken.

This is so that too many harsh tannins and oils from the pips and stalks

do not harm the wine. The boot illustrated here was a gift to the Library

by Dr Bryce Rankine.

Traditionally,

grape-treaders in Spain wear special cowhide boots, or Zapatos de pisar,

whose soles are heavily nailed with large-headed tacks driven into the

leather at an acute angle. This method of nailing gives results similar

to bare feet but with much less discomfort. The pips and stalks are trapped

undamaged between the nails and a soft layer of grapeskins forms over the

soles so that the hard pips and stalks of the other grapes cannot be broken.

This is so that too many harsh tannins and oils from the pips and stalks

do not harm the wine. The boot illustrated here was a gift to the Library

by Dr Bryce Rankine.

Sherry used to be one of the most widely made wine styles and in Sherryana by F.W.C. (Frederick William Cosens), illustrated by Linley Sambourne, published in London in 1886 even Australia is shown as getting into the act.

Journal of a tour through some of the vineyards of Spain and France (Sydney: Stephen and Stokes, 1833) by James Busby is a fascinating account of a three month trip mainly by stage-coach to find the right vine varieties for planting in Australia.

Portugal

Portugal is a small country with a remarkable diversity of wines. It is considered one of the most conservative wine countries in Europe and was the first to introduce the equivalent of a national system of appellation contrôlée the Douro in 1756. Portugal has nine traditional demarcated regions, as well as 26 new regions delimited with its entry to the European Common Market.

It

has a temperate maritime climate with warm summers and cool wet winters,

becoming more extreme in the south and east. Its landscape ranges from

the windy Atlantic coast to the wet northern hills to the dry inland areas.

Its grape varieties are similarly diverse, and it has some flavourful native

vines such as Touriga Nacional; Touriga Francesca and Tinta Roriz in the

Douro; and Baga in Bairrada. Its best known exported wine styles are port

and Mateus, a medium sweet, lightly sparkling wine, neither of which style

is as popular in its home country as overseas.

It

has a temperate maritime climate with warm summers and cool wet winters,

becoming more extreme in the south and east. Its landscape ranges from

the windy Atlantic coast to the wet northern hills to the dry inland areas.

Its grape varieties are similarly diverse, and it has some flavourful native

vines such as Touriga Nacional; Touriga Francesca and Tinta Roriz in the

Douro; and Baga in Bairrada. Its best known exported wine styles are port

and Mateus, a medium sweet, lightly sparkling wine, neither of which style

is as popular in its home country as overseas.

In the lush humid northern province, the Minho is synonymous with Vinho Verde or green wine. Grapes are traditionally hung high above the ground on pergolas grown with other crops, but this is making way for the more modern vineyard techniques.

To the east the steep fertile slopes of the Douro region with its slate-like poor schist soil produces one of the great fortified wines, port. It was developed by the British in the 17th century as an alternative to French claret. Port was based on a strong dry red wine made stronger by mixing with brandy to stabilize it for shipping. The technique was improved by stopping the fermentation with brandy while the wine was still sweet and fruity. Today port is one of the most strictly controlled of all wines, and falls into two groups: wood ports and vintage ports, as well as white port. The estates of the famous port houses are called quintas.

Alexander Henderson's The history of ancient and modern wines (London, 1824) has an overview of the Wines of Portugal, of which the first three pages are included here. He begins 'Since the commencement of the last century, the political relations of England and Portugal have rendered us extremely familiar with the wines of the latter country, and obtained for them a degree of favour and importance, which, under other circumstances, they could hardly have acquired...'.

Writing on Portugese wines was dominated by English writers in the 19th century.

In

1787 a member of the Croft family company of port shippers, John Croft,

wrote A

treatise of the wines of Portugal. The Library also has the first

Portugese translation Um

tratado sobre os vinhos de Portugal 2nd edition (Porto: Instituto

do Vinho do Porto, 1942). This highly sought-after work also has a dissertation

on the nature and use of wines in general imported into Great Britain.

In

1787 a member of the Croft family company of port shippers, John Croft,

wrote A

treatise of the wines of Portugal. The Library also has the first

Portugese translation Um

tratado sobre os vinhos de Portugal 2nd edition (Porto: Instituto

do Vinho do Porto, 1942). This highly sought-after work also has a dissertation

on the nature and use of wines in general imported into Great Britain.

Croft's was followed by a number of books by Joseph James Forrester, who was also an exporter of port. A word or two on port wine! (Edinburgh: The author, 1844) has the grand sub-title Addressed to the British publick generally, but particularly to private gentlemen; shewing how, and why, it is adulterated, and affording some means of detecting its adulterations, by one residing in Portugal for eleven years. Forrester, a prolific writer, strongly opposed the addition of brandy to port. In the pages included here he describes the grapes most used for port, including Bastardo, Tourigo and Tinto Grosso.

Another sought-after book is by prolific English wine writer Henry Vizetelly Facts about port and madeira: with notices of the wines vintaged around Lisbon, and the wines of Tenerife, published in 1880. It is a detailed journal of the author's trip to Portugal and Madeira in 1877 and is prized for its insightful text as well as its engravings of the region.

The Library has a reasonable number of books on wine in Portugese, which were purchased in the 1960s. Recently the Library purchased the impressive Portugese ampelography O Portugal vinicola: estudos sobre a ampelographia e o oenologico das principaes castas de videiras de Portugal by B.C. Cincinnato da Costa (Lisboa: Imprensa Nacional, 1900).

Madeira

Today Madeira is widely known yet widely neglected what has been termed a 'literary wine' with a fascination all its own, probably because of its origins on an exotic island and its legendary longevity.

Madeira is the largest of three small islands in the Atlantic ocean, 1,000k from Portugal and an autonomous part of Portugal. Being damp and sub-tropical it is a difficult place to grow grapes and most of the small island's vineyards are planted on tiny terraces called poios carved out of the red or grey basalt bedrock on its mountainous slopes.

Colonised by the Portuguese with its capital Funchal an important Atlantic trading post, Madeiran wine in the 17th century was found to improve on its long hot sea journey rolling across the Atlantic to the Americas in its sea-matured casks with added alcohol to help it survive. It improved even more on the even longer voyage through tropical waters to India.

To replicate these conditions on the voyages through tropical waters, Madeira is today made in different ways, but is based on the 'estufa' system of heating and artificially ageing the wine for a minimum of three months. The higher quality Madeiras are aged for years in huge wooden casks then stored in warm rooms with humidity produced by nearby hot water tanks. The wine is finally blended with fortified grape juice. Some makers leave their Madeira to age naturally, stored in warm rooms heated only by the sun, maturing in cask for at least 20 years, some for a century or more before bottling.

The heating and ageing before bottling means that exposure to air does not damage the Madeira when opened for many months. Fine Madeira can last for centuries, preserving layer upon layer of complex flavour. The original grape variety used was Malmsey (Malvasia): others used are Bual, Verdelho and Sercial, as well as the latest plantings of Tinta Negra Mole which is the principal variety since phylloxera arrived at the end of the 19th century.

Alexander Henderson's The history of ancient and modern wines (London, 1824) has an overview of the Wines of Madeira, of which the first three pages are included here. He says about the vines that 'the mildness of the climate and the volcanic soils with which that island abounds, were so favourable to their growth, that, if we may credit the report of the Venetian traveller, Alvise d Mosto, who stopped there on his voyage to Africa in 1455, they produced more grapes than leaves...'.

Henry Vizetelly's Facts about port and madeira: with notices of the wines vintaged around Lisbon, and the wines of Tenerife (London: Ward, Lock & Co., 1880) was the result of a visit by Vizetelly and his son to Portugal, Madeira and Tenerife in the Canary Islands. It is illustrated with engravings from original sketches by his son or from photographs, and is an interesting account of these wine areas.

Madeira became very popular in the 19th century, particularly in America, and A madeira party by Silas Weir Mitchell (Sacramento: Corti Brothers, 1975) is a fictional account of a madeira tasting in Philadelphia.

Greece

The

ancient Greeks were great vine growers, exporting their wine in exchange

for other products. Greece's climate and largely alkaline soil, in some

places volcanic, are very good conditions for vine growing. Alexander Henderson's The

history of ancient and modern wines (London, 1824) talks about the ancient

Greek wines and the 'black sweet wine' that Ulysses took with him to

the land of Cyclops. The Greek tradition going back 3,000 years of adding

pine resin during fermentation to produce retsina continues. Traces of

pine resin have been found in wine amphorae from earliest times. Attica,

the region of Athens, and the island of Euboea is the home of retsina,

although it can be made anywhere. Most is white, made from the Savatiano

grape, but some rosé or kokkineli is also made.

The

ancient Greeks were great vine growers, exporting their wine in exchange

for other products. Greece's climate and largely alkaline soil, in some

places volcanic, are very good conditions for vine growing. Alexander Henderson's The

history of ancient and modern wines (London, 1824) talks about the ancient

Greek wines and the 'black sweet wine' that Ulysses took with him to

the land of Cyclops. The Greek tradition going back 3,000 years of adding

pine resin during fermentation to produce retsina continues. Traces of

pine resin have been found in wine amphorae from earliest times. Attica,

the region of Athens, and the island of Euboea is the home of retsina,

although it can be made anywhere. Most is white, made from the Savatiano

grape, but some rosé or kokkineli is also made.

Since

Greece's move into the EEC in the 1970s, the modernisation process has

improved quality, together with a move toward grape varieties and systems

of control that will make fine wines. Of the red wines, the ancient Agiorgitiko

grape makes spicy wine, while Mavrodaphne from Patras makes a sweet dark

wine. Of the Greek islands, Crete is the biggest wine producer, famous

for its sweet Malmseys. Another island, Santorini, produces very dry white

wines on its volcanic heights; the sweet vinsanto of Santorini was once

a great industry, being the mass-wine of the Russian church.

Since

Greece's move into the EEC in the 1970s, the modernisation process has

improved quality, together with a move toward grape varieties and systems

of control that will make fine wines. Of the red wines, the ancient Agiorgitiko

grape makes spicy wine, while Mavrodaphne from Patras makes a sweet dark

wine. Of the Greek islands, Crete is the biggest wine producer, famous

for its sweet Malmseys. Another island, Santorini, produces very dry white

wines on its volcanic heights; the sweet vinsanto of Santorini was once

a great industry, being the mass-wine of the Russian church.

Alexander Henderson's The history of ancient and modern wines (London, 1824) has an overview of the 'modern' Wines of Greece, of which the first three pages are included here.

Cyrus Redding in his History and description of modern wines (London: Whittaker, Treacher, & Arnot, 1833) describes local winemaking customs, here talking about wines of Cyprus. "About five thousand jars of muscadine wine are made in Cyprus; the best at Agros. The sweetness of this wine is excessive; it drinks best at one or two years of age. It is clearer than that of most countries, and at first is white, but acquires a red colour and increase of body by age.. . . These wines, it is most probable, have undergone little or no change since the days of Strabo and Pliny, who reckon them among the most valuable in the world. Selim II conquered the island, that he might be master of them. At that time wines of eight years old were found, which it is said burned like oil. . . . After sixty or seventy years, some of this wine becomes as thick as syrup."

United Kingdom

The

main vinegrowing counties are Kent and Sussex, followed by Oxfordshire,

Dorset, Berkshire, Surrey and Somerset. The most popular vines

are the white Müller-Thurgau and Seyval Blanc, being early

ripeners and disease resistant. It goes without saying that the

least reliable factor in English winemaking is the weather. Nevertheless

there is a trademark English style developing described by Oz

Clarke in his Encyclopedia of wine as having 'a delicate,

hedgerow floweriness and fruit'.

The

main vinegrowing counties are Kent and Sussex, followed by Oxfordshire,

Dorset, Berkshire, Surrey and Somerset. The most popular vines

are the white Müller-Thurgau and Seyval Blanc, being early

ripeners and disease resistant. It goes without saying that the

least reliable factor in English winemaking is the weather. Nevertheless

there is a trademark English style developing described by Oz

Clarke in his Encyclopedia of wine as having 'a delicate,

hedgerow floweriness and fruit'.

The industry regulatory body is the English Vineyard Association which since 1978 has been empowered to grant a 'Seal of Quality' to wines submitted for its analysis and testing.

Wine has been in England since the days of the Roman occupation, and the Domesday Book mentions 42 vineyards. In the early middle ages the monastic vineyards of England were extensive and successful, but for various mainly political reasons they declined until something of a renaissance began in the 1950s, and in recent times winemaking has flourished.

Alexander Henderson's The history of ancient and modern wines (London, 1824) has an overview of the Culture of the vine in England, of which the first three pages are included here.

More than any other country, social and political history has modified the trading and drinking of wine in the United Kingdom. The Black Death halted urban wine commerce in Europe. In the 17th century cheap Portuguese wine entered the English market, then a popular craze for gin occurred in wine-drinking England in the early 18th century. Then Rhine wine (also known as hock) became popular, then madeira and then sherry.

For

much of its history, table wine was a luxury for the English,

or was an inferior product, as a result of high wine duties largely

targeted against the French. In the early 1860s Prime Minister

Gladstone made cuts to wine duties while extending wine licenses

to village grocery stores. Wine moved into the family dinner table

and created a new market. Imports of French wine more than tripled

from 1859 to 1861. In this new market there was an opportunity

for books on wine and Charles Tovey's Wine and wine countries

(London: Hamilton, Adams, 1862) was one of several books written

to educate the new consumer and the new grocer who could now sell

wine.

For

much of its history, table wine was a luxury for the English,

or was an inferior product, as a result of high wine duties largely

targeted against the French. In the early 1860s Prime Minister

Gladstone made cuts to wine duties while extending wine licenses

to village grocery stores. Wine moved into the family dinner table

and created a new market. Imports of French wine more than tripled

from 1859 to 1861. In this new market there was an opportunity

for books on wine and Charles Tovey's Wine and wine countries

(London: Hamilton, Adams, 1862) was one of several books written

to educate the new consumer and the new grocer who could now sell

wine.

The British may not be famous for their wines, but they have produced many of the great writers on wine.

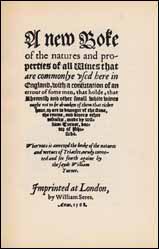

The

first complete book in English on the subject of wine was A

new boke of the natures and properties of all wines that are commonly

used here in England by William Turner published in London

in 1568. In addition to being the first single work in English

on wine, Turner's book was known to Shakespeare, and was almost

certainly a source of wine information for the plays. Turner was

a distinguished botanist and physician with an interest in viticulture

and winemaking and also in the effects of wine and its use in

medical practice. He firmly believes that white Rhine wines can

relieve kidney and bladder stones, and in support quotes classical

writers from Galen onwards. The Library has a facsimile reprint

(New York: Scholars' Facsimiles & Reprints, 1941) with a modern

English text, which is a collector's item in its own right.

The

first complete book in English on the subject of wine was A

new boke of the natures and properties of all wines that are commonly

used here in England by William Turner published in London

in 1568. In addition to being the first single work in English

on wine, Turner's book was known to Shakespeare, and was almost

certainly a source of wine information for the plays. Turner was

a distinguished botanist and physician with an interest in viticulture

and winemaking and also in the effects of wine and its use in

medical practice. He firmly believes that white Rhine wines can

relieve kidney and bladder stones, and in support quotes classical

writers from Galen onwards. The Library has a facsimile reprint

(New York: Scholars' Facsimiles & Reprints, 1941) with a modern

English text, which is a collector's item in its own right.

Philip Miller's The gardeners dictionary of 1731 is probably the first book in English to discuss vine varieties. In those days wine was the everyday beverage throughout much of Europe and so was treated as part of agricultural husbandry generally. Philip Miller was gardener for the Chelsea Physic Gardens and was the most respected gardener of his era. The full title of his work is as impressive as the work itself The gardeners dictionary: containing the best and newest methods of cultivating and improving the kitchen, fruit, flower garden, and nursery; as also for performing the practical parts of agriculture: including the management of vineyards, with the methods of making and preserving the wine ... together with directions for propagating and improving from real practice and experience, all sorts of timber trees. The Library holds the seventh edition of 1759 which contains 20 pages on wine and 40 pages on viticulture.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Other European Countries

Switzerland

Switzerland's

vineyards are concentrated around the country's lakes and rivers

and tend to be steep and terraced, the high cost of which makes

their wines expensive. In the early 1990s an Appellation Contrôlée

system began to be applied. The country is divided into 23 cantons,

all of which produce some wine. Most wine comes from the Swiss

romande, the French-speaking area overlooking Lake Geneva and

the Rhône, as well as from Neuchâtel and Geneva. The

white Chasselas is the main variety making light fresh wines,

while the reds are made from Pinot Noir and Gamay.

Switzerland's

vineyards are concentrated around the country's lakes and rivers

and tend to be steep and terraced, the high cost of which makes

their wines expensive. In the early 1990s an Appellation Contrôlée

system began to be applied. The country is divided into 23 cantons,

all of which produce some wine. Most wine comes from the Swiss

romande, the French-speaking area overlooking Lake Geneva and

the Rhône, as well as from Neuchâtel and Geneva. The

white Chasselas is the main variety making light fresh wines,

while the reds are made from Pinot Noir and Gamay.

The Festival of the Vignerons of Vevey has been held in the Swiss town of Vevey irregularly since the mid 17th century. It is the world's most important Wine-Growers' Guild. Vevey is on Lake Geneva between Lausanne and Montreux. Chasselas is the main grape variety grown, producing a dry, robust white wine. The Library has many of the much sought-after publications emanating from the Festival. La Fete des vignerons 1955: album commemoratif by Guy Burnand (Lausanne: Payot, 1956) is a photographic celebration of this unique wine event and an explanation of the ancient ceremonies.

Austria

Austria is divided into three main regions: Lower Austria, Burgenland and Styria, mainly producing white wine. The vineyards are concentrated in the east of the country. From the north come outstanding sweet wine, elsewhere are bone dry wines of body and elegance. Austria is also famous for its wine glasses made by migrants from Bohemia.

Hungary

There are vines nearly everywhere in Hungary and quality is improving with Western investment. In the north are produced light, crisp, fruity Sauvignon Blancs and Chardonnays in the international style. The local taste in whites is sweet and spicy, made from Olasz Rizling, Leanyka, Tramini and others. The south is the main area for red wine, made from Kadarka, Merlot and Pinot Noir. Hungary is probably best known for its sweet wines from the Tokaji vineyards.

Wine is also made in Bosnia, Bulgaria, Crimea, Croatia, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Georgia, Kosovo, Luxembourg, Macedonia, Moldova, Montenegro, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Turkey, Ukraine and Vojvodina.

The topography of all the known vineyards ... by Andre Jullien (London, 1824) has a chapter on Russia which covers Caucasus, Georgia, Crimea, Don, and Saratop.

Copyright and this website | Disclaimer | Privacy | Feedback | Accessibility | FOI ![]()

![]()

![]()

The Romans established what are

now all the highest quality vineyard areas Burgundy, Bordeaux, Champagne

and the Loire with the exception of Alsace, so French wines have developed

their identities over almost 2,000 years.

The Romans established what are

now all the highest quality vineyard areas Burgundy, Bordeaux, Champagne

and the Loire with the exception of Alsace, so French wines have developed

their identities over almost 2,000 years.

The

discoveries and ideas of three French writers of the 19th century on technical

aspects of wine production are still used today. They are Louis Pasteur,

Jean-Antoine Chaptal and Dr Jules Guyot.

The

discoveries and ideas of three French writers of the 19th century on technical

aspects of wine production are still used today. They are Louis Pasteur,

Jean-Antoine Chaptal and Dr Jules Guyot.

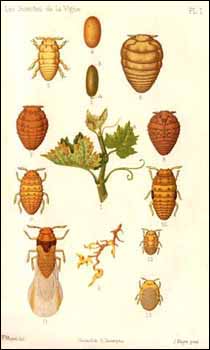

Another

19th century discovery was the effect of the phylloxera louse, which arrived

from America and devastated European vineyards until appropriate control

measures were found. In France over 2 million hectares, or 6 million acres,

of vineyards were destroyed, causing trauma for individual vinegrowers

who watched their vines dying before their eyes, as well as major social

and economic impact in Europe. The illustration of phylloxera shown here

is from

Another

19th century discovery was the effect of the phylloxera louse, which arrived

from America and devastated European vineyards until appropriate control

measures were found. In France over 2 million hectares, or 6 million acres,

of vineyards were destroyed, causing trauma for individual vinegrowers

who watched their vines dying before their eyes, as well as major social

and economic impact in Europe. The illustration of phylloxera shown here

is from  In

1846 an English professor and freemason, Charles Cocks, published Bordeaux,

its wines and the claret country in English. It was the most comprehensive

classification of a wine area that had yet appeared. In 1850 a Bordeaux

bookseller, Michel Féret, rechecked and slightly changed the classification

and published the first French edition. In 1855, as a response to a demand

from Napoleon III, Cocks and Féret's work was adopted as and still

is the official classification of all the wines of Bordeaux and is known

as 'The Bordeaux Bible' The enormous volume, which today lists some 7,000

properties, is updated roughly every ten years. The Oxford companion

to wine regrets that the book is 'now sadly neglecting its English

roots and published simply as Féret'. The Library holds a number

of editions from 1883 to the 15th edition of 1995 with 2012 pages. Shown

here is the 2nd English edition

In

1846 an English professor and freemason, Charles Cocks, published Bordeaux,

its wines and the claret country in English. It was the most comprehensive

classification of a wine area that had yet appeared. In 1850 a Bordeaux

bookseller, Michel Féret, rechecked and slightly changed the classification

and published the first French edition. In 1855, as a response to a demand

from Napoleon III, Cocks and Féret's work was adopted as and still

is the official classification of all the wines of Bordeaux and is known

as 'The Bordeaux Bible' The enormous volume, which today lists some 7,000

properties, is updated roughly every ten years. The Oxford companion

to wine regrets that the book is 'now sadly neglecting its English

roots and published simply as Féret'. The Library holds a number

of editions from 1883 to the 15th edition of 1995 with 2012 pages. Shown

here is the 2nd English edition  Burgundy

Burgundy Clos

de Vougeot is a famous walled vineyard in Burgundy created by monks of

Cîteaux. It was taken over by the Cistercian monks until the French

Revolution, when all clerical estates were dispossessed. Today Clos de

Vougeot is a major tourist attraction and is also home to the Confrérie

des Chevaliers du Tastevin. The Library holds Rene Garraud's Notice

sur le Clos de Vougeot: le phylloxera au XVe siecle (Citeaux: Cote-d'Or,

Imprimerie et Librairie, 1888).

Clos

de Vougeot is a famous walled vineyard in Burgundy created by monks of

Cîteaux. It was taken over by the Cistercian monks until the French

Revolution, when all clerical estates were dispossessed. Today Clos de

Vougeot is a major tourist attraction and is also home to the Confrérie

des Chevaliers du Tastevin. The Library holds Rene Garraud's Notice

sur le Clos de Vougeot: le phylloxera au XVe siecle (Citeaux: Cote-d'Or,

Imprimerie et Librairie, 1888).

Champagne

Champagne Some

of the most individual white wines in France come from Alsace, which despite

its association with Germany is fiercely French. The eastern mountain ranges

of the Alsace area are known as the 'slope zone' and produce spicy perfumed

white wines unlike any other. The Vosges mountains slope into the Rhine

valley and their east-facing vineyards stay warm and dry well into autumn.

The Jura further south and the Savoie also produce sharp tasy whites. Included

here from

Some

of the most individual white wines in France come from Alsace, which despite

its association with Germany is fiercely French. The eastern mountain ranges

of the Alsace area are known as the 'slope zone' and produce spicy perfumed

white wines unlike any other. The Vosges mountains slope into the Rhine

valley and their east-facing vineyards stay warm and dry well into autumn.

The Jura further south and the Savoie also produce sharp tasy whites. Included

here from  Rhône

Rhône