The State Library

of South Australia has the largest collection of wine literature

in the southern hemisphere and one of the biggest in the world.

Its origins date back to 1834, two years before the first European

settlers arrived in the colony. The collection ranges from an

eleventh century manuscript leaf to recently published books and

magazines, to wine labels, wine lists and diaries of winemakers,

and to books in many languages. This theme features twelve of

the State Library’s most precious wine records.

Punishments

for drunk monks 1000 years ago

Decretum. By

Burchard of Worms

Germany, first half of the eleventh century. Decretum. By

Burchard of Worms

Germany, first half of the eleventh century.

This is part of a manuscript leaf

from a manual for the instruction and guidance of young monks, written

in a German monastery a thousand years ago. The language is Latin

and the script Carolingian, on which is based some of the most beautiful

printing types still in use today. It contains punishments for drunk

monks - fifteen days on bread and water if one drank so much that

one vomited; thirty days on bread and water if one, when drunk,

encouraged others to get drunk; and forty days on bread and water

if, through drunkenness, one vomited the communion wine and sacred

host.

Wine

in the classical world and a classic of

printing Wine

in the classical world and a classic of

printing

Pliny’s Natural

history. Venice

1472.

The Library’s

oldest original printed book with winegrowing

references is this remarkable encyclopaedia

of the ancient world, which was the major

source for most mediaeval knowledge. Printed

in Venice in 1472 by the influential type

designer, printer, and publisher, Nicolaus

Jenson, some 17 years after the first book

was printed in Europe from moveable type,

this most handsome volume is full of information

on wine-growing in ancient times.

For

those who cannot read Latin, the following

is a translation.

Pliny’s Natural

history London: Bohn, 1855-1857,

vol.3

Wine

and prayer

Book

of hours. Paris, 1490.

Books of

Hours were the personal prayerbooks of

the laity and have been described as "late

mediaeval best-sellers". Those produced

by hand during the later Middle Ages and

the Renaissance were often elaborately

decorated, and might include beautiful

miniature pictures depicting the occupation

for each month of the calendar year: the

occupation usually chosen for March was

ploughing and pruning and for September

treading the grapes.

Book

of Hours. Paris, 1490. This

exquisitely illustrated work was written

and decorated by hand on vellum in

Paris in about 1490. Among its brilliantly

coloured miniatures is one for September,

which shows a person treading grapes.

In addition to the treader and someone

pouring grapes from a basket into a

vat, a worker in the background enjoys

a surreptitious tipple, adding a humorous

touch. It is on permanent loan to the

State Library of South Australia from

the Anglican Diocese of Adelaide.

The vivid

and richly detailed miniatures, which appeared

in the calendar of the Trés

riches heures du Duc de Berry, were

begun early and finished late in the fifteenth

century for Jean, Duc de Berry. The miniature

for March shows three peasants trimming

vines within an enclosure, with more vineyards

on the right. For September, we see the

grape harvest at the foot of the Château

de Saumur. The original book is in the

collection of the Musée Condé,

Chantilly.

First

edition of the first wine book

Vinetum,

by Charles Estienne. Paris, 1537 First

edition of the first wine book

Vinetum,

by Charles Estienne. Paris, 1537

Although

Arnaldus de Villanova’s Liber

de vinis, published in 1478, is often

said to be the earliest printed book on

wine, it dealt mainly with the supposed

physical effects of wine, and its perceived

ability to cure poor memory, jaundice or

melancholy, rather than with winegrowing.

The earliest

book devoted to grapegrowing and winemaking

was Vinetum, by Charles Estienne,

first published in Paris in 1537 and republished

many times. Written in Latin, surprisingly

this landmark book has not been translated

into English. It includes a table of French

wines and wine regions, with their Latin

and French names, some of which – Beaune,

Beaujolais, Champagne, Bordeaux – are

clearly identifiable.

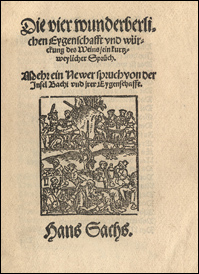

The

four wondrous properties of wine and

their effects The

four wondrous properties of wine and

their effects

Die

vier Wunderberlichen Eygenschafft und Wurckung des

Weins…, by Hans Sachs.

Nuremberg : Georg Merckel, 1553.

This very

scarce pamphlet describes "the four wondrous

properties of wine and their effects".

The opening paragraph, here translated

by Professor Ralph Elliott, gives an indication

of the tenor of this entertaining work:

One

day I asked a doctor to tell me whence

derives the power of wine to affect in

four different ways whomever it overcomes

so that his mood changes. The first he

makes peaceful, benevolent, mild and

kind. Others he arouses to anger, so

that they storm and quarrel and rage.

The third he makes crudely childish and

shameless, while the fourth is led by

the wine to fantasies and follies.

He

said, I will tell you. The wise pagans

describe how after the Flood had

passed, Lord Noah began to plant

vines before anything else. But the

soil was unfruitful, so old Noah

cleverly fertilized it with manure

which he took from different animals,

namely sheep, bears, pigs, and monkeys.

With this he manured his vineyard

all over, and when the wine was ready

it had acquired the natures of the

four animals, properties which it

still possesses. Now God made all

men of four elements, air, fire,

water, and earth, as Philosophy confirms,

and according to each man’s

nature, so does wine affect him. namely sheep, bears, pigs, and monkeys.

With this he manured his vineyard

all over, and when the wine was ready

it had acquired the natures of the

four animals, properties which it

still possesses. Now God made all

men of four elements, air, fire,

water, and earth, as Philosophy confirms,

and according to each man’s

nature, so does wine affect him.

Hans Sachs,

who died in Nuremberg in 1576, was a member of

the Meistersinger Guild, and the subject of Wagner’s

opera, The Mastersingers of Nuremberg.

Wine

cures gout

The

juice of the grape, by Dr. Peter Shaw.

London 1724.

Shaw, a

London physician, and an early advocate

of the medicinal benefits of wine, claims

that wine cures everything from smallpox

to venereal disease, including gout. This

copy, beautifully bound with its spine

and corners in calfskin, comes from the

library of the great twentieth-century

wine writer, André Simon, and contains

his elegant bookplate. Simon found the

work "very amusing".

Finding

words to convey flavours Finding

words to convey flavours

The

history of ancient and modern wines, by

Alexander Henderson. London, 1824.

This is

probably the first book in the English

language to give anything like an accurate

account, based on some personal travelling,

of the wines of Europe and also of Persia

and the Cape of Good Hope. Henderson, a

doctor, describes a problem common to today’s

wine writers and consumers – how

to find words to convey flavours. Many

of his observations on "modern wines" are

still valid.

Grapes

have family histories, too Grapes

have family histories, too

Ampélographie

française, by Victor Rendu. Paris,

1857

Ampelographies

describe and often illustrate grape varieties.

The hand-coloured lithographs of Eugene

Grobon make this book possibly the most

prized of the great ampelographies of the

nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

A fête worth waiting for A fête worth waiting for

Album

officiel de la Fête des Vignerons. Paris,

1889

One of

a rare and spectacular series of works

describing and illustrating the Fêtes

of the Vignerons of Vevey, which have been

held in the Swiss town of Vevey irregularly

since the mid-seventeenth century. They

are now held roughly once in a generation.

It is the world’s most important

wine festival, and is a development of

the activities of the mediaeval Wine-Growers’ Guild.

Each fête generates a number of sought-after

publications including a fold-out album,

or leporello, which could be up to seven

metres long. Vevey is on Lake Geneva between

Lausanne and Montreux. Chasselas is the

main grape variety grown, producing a dry,

robust white wine.

Australia's

first wine book Australia's

first wine book

A

treatise on the culture of the vine and the art of

making wine, by James Busby. Sydney, 1825

Australia’s

first wine book was written a year after

its 24-year old author arrived in New South

Wales. Based on the ideas of French writers

it was intended to show "the respectable

portion of the community" how to produce

wine and thus to give value to tracts of

land which otherwise "would in all probability

remain for ever useless". But Busby also

regarded viticulture as fitted "to increase

the comforts, and promote the morality

of the lower classes of the Colony" – a

theme which persists through much of Australia’s

nineteenth-century oenography. Busby also

predicted that wine would supply "the great

desideratum of a staple article of export,

to which the colonists of New South Wales

might be indebted for their future prosperity".

He is known as the father of Australian

viticulture.

Leo

Buring's journal Leo

Buring's journal

Leo

Buring’s journal of a visit to the vineyards

and cellars of Germany and France in 1896.

Buring

spent time at Schloss Johanissberg and

at Geisenheim on the Rhine: the world-famous

wine school at Geisenheim had been founded

in 1872. Buring’s unpublished notes,

some in English, others in French, are

full of practical details, as well as occasional

impressions of wines tasted.

Valmai Hankel

Valmai

Hankel was Senior Rare Books Librarian

at the State Library of South Australia

until she retired in June 2001, and has

a particular interest in the literature

of wine and its history. She even coined

a word, ‘Oenotypophily’, which

she takes to mean "love of wine and print" to

describe this obsession. Valmai

Hankel was Senior Rare Books Librarian

at the State Library of South Australia

until she retired in June 2001, and has

a particular interest in the literature

of wine and its history. She even coined

a word, ‘Oenotypophily’, which

she takes to mean "love of wine and print" to

describe this obsession.

She has

been wine writer for the monthly publication, The

Adelaide Review, since October 1995,

writes a column on wine history for the

national magazine, Winestate, and

has inaugurated an occasional column, "Oenotypophily",

for the magazine The Australian and

New Zealand Wine Industry Journal. She

firmly believes that wine books from the

past have much that is both relevant and

entertaining to say to us today, and spends

a fair bit of time in both writing and

public speaking trying to convince others

of this. The pamphlet, Oenography: words

on wine in the State Library of South Australia,

is believed to be the first publication

of the Australian Bureau of Statistics

not to contain a single statistic.

As well

as drinking more good wine than she should,

she has been an associate judge at South

Australia’s McLaren Vale Wine Show

on three occasions, and was chairman of

the consumer panel for the Advertiser-Hyatt

South Australian Wine of the Year Award

for five years. |

Wine

in the classical world and a classic of

printing

Wine

in the classical world and a classic of

printing

The

four wondrous properties of wine and

their effects

The

four wondrous properties of wine and

their effects namely sheep, bears, pigs, and monkeys.

With this he manured his vineyard

all over, and when the wine was ready

it had acquired the natures of the

four animals, properties which it

still possesses. Now God made all

men of four elements, air, fire,

water, and earth, as Philosophy confirms,

and according to each man’s

nature, so does wine affect him.

namely sheep, bears, pigs, and monkeys.

With this he manured his vineyard

all over, and when the wine was ready

it had acquired the natures of the

four animals, properties which it

still possesses. Now God made all

men of four elements, air, fire,

water, and earth, as Philosophy confirms,

and according to each man’s

nature, so does wine affect him.

Finding

words to convey flavours

Finding

words to convey flavours Grapes

have family histories, too

Grapes

have family histories, too A fête worth waiting for

A fête worth waiting for

Leo

Buring's journal

Leo

Buring's journal Valmai

Hankel was Senior Rare Books Librarian

at the State Library of South Australia

until she retired in June 2001, and has

a particular interest in the literature

of wine and its history. She even coined

a word, ‘Oenotypophily’, which

she takes to mean "love of wine and print" to

describe this obsession.

Valmai

Hankel was Senior Rare Books Librarian

at the State Library of South Australia

until she retired in June 2001, and has

a particular interest in the literature

of wine and its history. She even coined

a word, ‘Oenotypophily’, which

she takes to mean "love of wine and print" to

describe this obsession.